How to Make a Living as an Artist

Preface

I first wrote down these ideas in early 2017, just after I started to make a living as an artist. I came to them over time, but I wanted to document them at that specific moment in my career. The moment when I was finally sure that what I was doing was working. I had just finished a year with $54k in sales and was about to have one with $150k. A few years later I would sell over $1M in art. I figured that whatever I was thinking at that moment of transition would be the most relevant to other aspiring artists.

I didn't get into art to make a living — I got into it as a creative outlet while feeling trapped in my job. But as I continued to want to make more art, I developed theories on how to earn enough money to buy the remainder of my time so I could work exclusively on art.

I have shared these writings with artists who have come to me for advice. I have not before now published them due to some combination of busyness and fear of criticism.

Why You Should Not Make a Living as an Artist

Most people who enjoy making art should not try to make it their full time job. When you turn an avocation (hobby) into a vocation (job) you have to do new things you do not enjoy. Emails, events, meetings, accounting, and more. These are not only a drag but can actually strip the joy from the rest of your art practice.

Even the work itself can become a burden because you now have to make it. Amateurs can wait for inspiration; professionals must create every day.

If you enjoy making art, ask yourself why that is not enough? Why do you need to make money from this activity? Why do you need to do it with more of your time? Can it not perhaps give you more joy remaining a hobby?

I have played the drums for many years, and while I was once tempted to go pro, I have always resisted. Drumming is a refuge for me. A joy. An escape. I play when I want. I don't play when I don't want. This is no longer true for my painting. Beware. Think hard.

What Next

This essay has three parts, each of which can stand alone: "Admit It's a Business", "Finding Your Style", and "Brand and Repetition". If people like these, I would be happy to write more.

Admit It's a Business

The number one mistake I see artists make is not accepting that they run a business. If you cannot accept and even embrace this simple fact, you are totally hosed. It is hard to start a business; it is way harder to do it by accident.

Artists Are Solopreneurs

Making your challenge more difficult is that artists are usually not just entrepreneurs but solopreneurs. There is rarely enough money in art to support even a single person, so we do not get to specialize as one might in high tech entrepreneurship, in which it is totally common to have one co-founder focus on product and another on sales. Most people, at least at first, must do it all. Most artists do not want to do it all. They want to just make art. I am sorry. Some people have a gallery or life partner who acts as a business partner. But most of the time, there is no one to help you. You must think about your art practice as a business.

Business Is a Lens

"Business" is simply a lens through which one can look at something. It is not the only lens. You can look at art through an aesthetic lens (how does it look?), a technical lens (how is it made?), an emotional lens (how does it make you feel?), an interpretive lens (what does it mean?), and a political lens (what does it say about our world?).

Thinking or talking about the business of your art can feel weird, as you probably didn't get into making art to make money. But as Walt Disney said, "We don't make movies to make money, we make money to make movies". The goal of thinking of your art practice like a business is to help you make more art.

Every artist who is making a living is running a business, and their practice can always be evaluated through a business lens. "Business" is simply a set of concepts that help you understand how money is made and spent. This is entirely relevant to the goal of making a living as an artist.

Same Knobs, Different Configurations

The breakthrough realization for me was that all businesses are fundamentally similar. They have the same knobs just configured differently. The knobs are things like product, sales channels, marketing, PR, and brand. A jeweler might have high material costs (gold and diamonds), an artist moderate material costs (paint and canvas), and a greeting card company low material costs (paper), but they all have "material costs". These knobs are what you see through the business lens, and when approached this way it is clear that there is nothing magical about being an artist — it is simply a different configuration of those knobs. Ultimately what you are looking for is a business model — a configuration of the knobs — that is profitable enough to support one employee, you.

Many Paths

There are many ways to make money as a visual artist. From the outside it seems like there is only one: get a gallery to represent you, and have them sell a small number of high priced works to a niche group of wealthy collectors. This model is viable, but it has gatekeepers (e.g. gallerists), and it only works for a small number of people. I was not one of them. Galleries have as yet not significantly advanced my career.

Do not wait around to be chosen. Just because you do not have gallery representation does not mean you cannot make a living as an artist. I have seen artists sell their work on websites, through social media, at open studios, at farmer's markets, at parties, and from apartments. I have seen artists make a living by winning government grants, from corporate commissions, and from wealthy patrons. I have seen artists sell paintings, prints, t-shirts, and pins. Many artists make a living not by selling their art but by using their artistic skills to teach, run workshops, or create commercial art (work created by you but designed by someone else, usually for a commercial purpose).

There are many paths to making a living as an artist. The path that works for a doodle artist will be different than for a photorealistic painter.

The Fog

I did not know how I would make a living when I began making art. I felt like I was in a fog, groping around, and trying things. Doing this caused the fog to dissipate until it was clear how I would make a living. I personally make a living selling relatively affordable paintings, made from editions, through an email list. This was not at all obvious when I started. I tried a lot of things. My goal was never to not make mistakes but to not make the same mistake twice. Slowly you will learn what works and what does not. What works for me might not work for you. The search is the same, but the outcome might not be.

Strengthen the Muscle

The first year I sold paintings I made a laughably small amount of money from my art. I was working another job that paid well, and I asked myself whether it was worth selling art at all. I decided to push on because I view selling art like strengthening a muscle. You start off weak, but if you keep at it, you will get stronger over time.

Picasso said, "In the beginning, I did not sell at a high price, but I sold. My drawings, my canvases went. That's what counts."

There are so many things to get better at — where to sell your work, how to price your work, how to ship your work, how to talk to collectors, and even what work to make. If you have no idea how to do these things, do not worry, just make a sale and learn from the experience.

The first time someone asked to commission a painting from me, I quoted him $100. The painting took me several days, putting my effective hourly earnings well below minimum wage. Was I upset? No. Did I ask for more money? No. But the next time someone asked to commission a painting, I quoted $500. That's strengthening the muscle.

Many artists make a living by creating unique works that they sell through galleries. I tried this in 2016. I made five large pieces entirely of my own conception and showed them in a gallery that would have taken 50% of each sale. None of them sold. At the same time I made those works I made another five large works on commission. These had been pre-sold at higher prices, and I kept 100% of each sale. Five works I had already sold for more than twice the income of those I had hoped and failed to sell? A clear lesson. Was I upset? No. But for the next five years I did not create a single unique work for a gallery and instead made them only on commission. That's strengthening the muscle.

While you can learn from failures, only sales strengthen the muscle because only they show that someone actually cares about what you are making. Also only sales permit you to practice the myriad other skills required to make a living as an artist beyond simply making art.

Finding Your Style

The second most common mistake I see artists make is creating work that people do not want to buy.

Image-Market Fit

There is a concept in entrepreneurship called Product-Market Fit. It exists when you create something that people want. This sounds easy to do, but it is not, and the vast majority of startups never do it. How do you know if you have Product-Market Fit? If you have to ask, you don't.

I have found something similar in art, which I call Image-Market Fit. This is achieved when you create art that people want. It will not be subtle when it happens.

The first stencil painting I made was a swan on a canvas. No one cared. Then a penguin, then an origami bird. The only buyer was my father.

Then I painted dog walkers on the sidewalk in a local dog park. Then I painted lips on a crosswalk. Then a Dr. Seuss fish falling down the stairs into a transit station.

And then finally a Honey Bear on a park wall.

While people liked my earlier projects, the response to the Honey Bear was markedly different. In the three days before the city removed it, I watched a group of school children scream "Honey Bear!" when they noticed it. I saw a girl demand her mother stop and take a photo of her with it. An Instagram influencer shared it with her tens of thousands of followers. This photo eventually ended up (without my permission) in a book in Urban Outfitters. That is Image-Market Fit.

One of the biggest mistakes I see artists make is painting things that don't resonate with people. Once you have an aesthetic that works, the market rewards you for exploring adjacent aesthetic territory. You might not make a living right away — it took me over two years from when I painted that first Honey Bear until I took my art full time — but it is totally necessary if you are to make a living off your own art (as opposed to teaching or commercial art). Until then, if what you're doing isn't resonating, you just need to just paint something else. Experiment with different concepts and directions until you find something that works.

Art as the Expression of Your Soul

My exhortation to make different art until you find Image-Market Fit might sound cold and calculating. Doesn't art come from my soul? If my work is an expression of my soul, how can I just abandon it and make different work?

If you are pursuing art as a hobby and creating work for personal enjoyment, absolutely you should create whatever moves you. Create the exact same kind of work over and over. Or create something totally new and different every time. None of that matters; all that matters is that you enjoy the process and find personal satisfaction. See "Why You Should Not Make a Living as an Artist" above. But if you want to be a professional artist, repeatedly creating work that people do not want is lunacy.

To the question, "how can I abandon what is in my soul?", I say, "Is that all that is in your soul?". We have the ability to express ourselves in many ways and through many mediums. Picasso worked in realism, cubism, and surrealism. He had a Blue Period, Rose Period and African Period. He worked in painting, drawing, printmaking, and ceramics. All of those were in his soul. Some of them resonated with the public more than others.

I am not saying you should attempt to pander to the masses, and in fact I do not believe this works (more on that below), but you should explore your interests until you find something that interests other people as well.

To state this again. There are a set of things that excite you artistically, and there are a set of things that the public enjoys, and you are looking for something in the intersection of those two sets. You can make work that is commercially successful while still staying true to your artistic interests.

British street artist SHOK-1 started painting graffiti in 1984 seemingly without the intention of becoming a professional artist. He says, "I had chapters and chapters and chapters of different bodies of work before I came to the x-ray thing. But the x-ray thing, for whatever reason, [has] become very visible. I didn't intend that. [...] Seriously I had no idea".

His x-ray series immediately resonated, propelling him to international recognition and sold-out shows and editions... after 20+ years of painting. That is Image-Market Fit.

You Don't Know the Market

I want to state again that I do not believe you should paint what you think people will like. I do not believe this works because I do not believe you can know what people will like. I certainly do not, and from my observations, I do not believe anyone does. The only way to find out what the market likes is to go to the market.

My approach is to paint things that I like and trust that my taste is good enough to get hits every now and then.

The Beatles wrote 227 songs, but only 34 hit the Top 10. Do you think they would put out a song that they didn't believe could be a hit? Mozart wrote over 600 songs, but only about 50 of them are widely played. Do you think he purposefully wrote duds? Of course not. Both the Beatles and Mozart made work that interested them, and occasionally those works resonated with other people.

I have experienced this so many times. When I did the second iteration of my Dog Walker series, I was super excited about my origami corgi. I thought it was perhaps the best thing I had ever painted. No one cared. Not once has someone asked to buy or commission one. Conversely, I did not think my California Poppies were going to be popular because they are one of my simplest designs. But my first post of them to Instagram quickly became one of my most liked, and I have been commissioned to paint several poppy murals.

I don't know. You don't know. Don't try to know. Just make art that excites you, and make enough of it that you eventually make work that resonates with people.

As a final note, if you make something that you like, at least one person will like it — you. If you make something you think other people will like, you run the risk of no one liking it at all. That would be sad.

You Are Not Your Art

Art is absolutely an expression of yourself. But your art is not you. Try not to entangle your ego with your art. If someone does not like your art, that does not mean they do not like you. If they think your art is bad, that does not mean they think you are bad.

I often paint things that fall totally flat. Sometimes this happens with the works about which I am the most excited. That's life. If you are unable to get over this form of rejection, you will be unable to push forward and make something that truly resonates.

I have heard this approach referred to as "shots on goal" — the more shots you take, the more likely you are to succeed. If you are too scared to show your work to anyone or too defensive about the feedback you receive, you will have fewer shots on goal and thus less chance of making a living as an artist. Based on the numbers above, only 12% of Beatles songs were hits, and only 8% of Mozart's. But they took a lot of shots on goal!

Brand and Repetition

The key to making money as an artist is having a brand. Most of art's value is brand value.

Three Levels of Branding

I believe artistic branding has three tiers, each more valuable than the last.

The first level is the branding of an image. Most people know me because I paint Honey Bears. They also might know me because I paint lips or poppies. The images and the way I paint them are recognizable, and when you see them, you think of me.

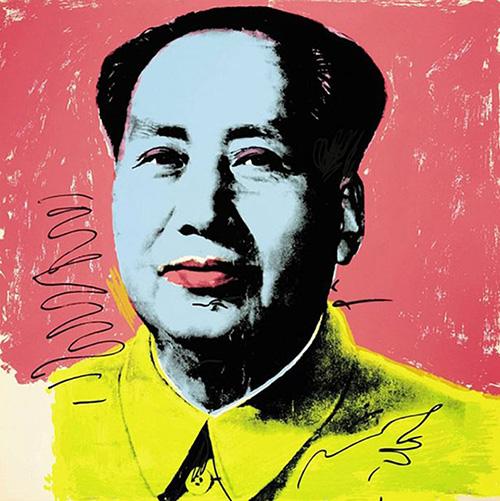

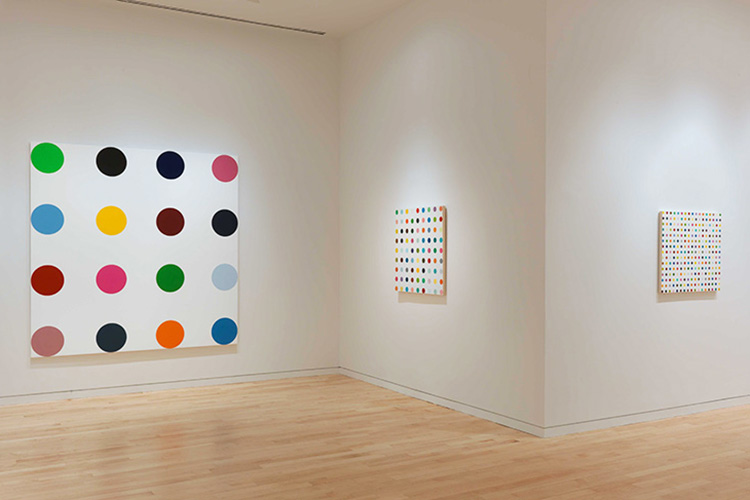

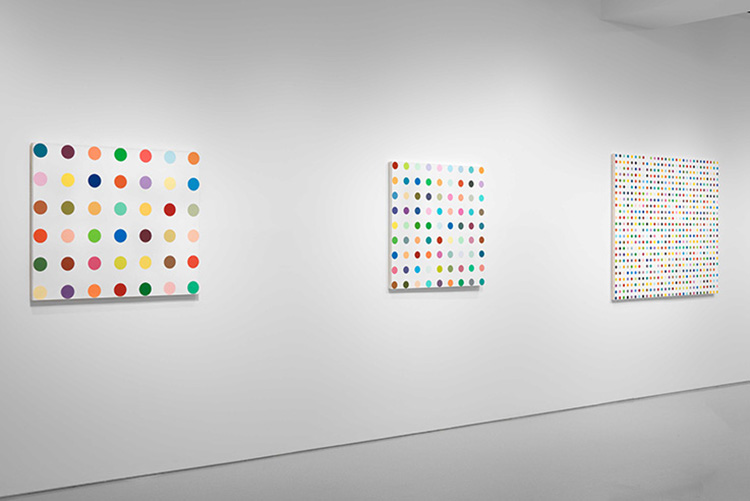

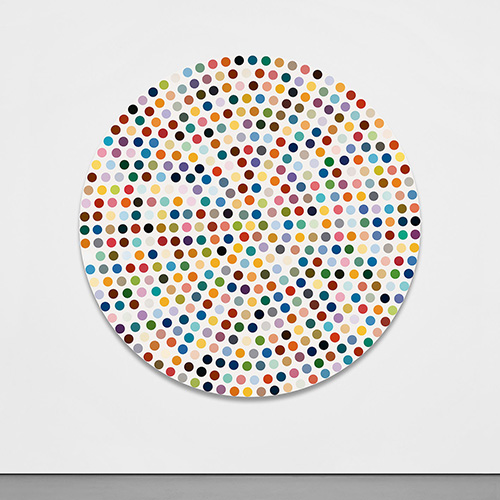

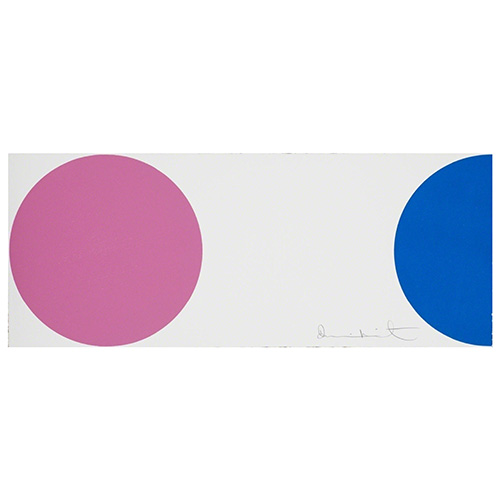

Similarly, when you see a spot painting, you think Damien Hirst. A pond with waterlilies, Monet. And the Radiant Baby, Keith Haring.

For more contemporary examples from street art: JC Rivera paints Bear Champ, Pursue paints Bunny Kitty, and STIK paints stick figures.

The next level is the branding of a style. This is sometimes called "the hand of the artist", and it is a recognizable style that goes across multiple images. When you see a painting from Keith Haring, you know immediately that it's a Haring. He can paint any image, and it is clear it's him.

Same goes for Georgia O'Keeffe.

Same goes for Andy Warhol.

One contemporary examples is Pichiavo.

Another contemporary example is Kobra.

You can immediately tell a work is from one of these artists, even if you haven't seen that particular image before.

I hope that I have or am branding my style and that it is recognizable between my Honey Bears, birds, flowers, and other subjects.

The final level is the branding of a name. People buy a painting because it is a "Koons", "Hirst", "Banksy", "Warhol", or "Picasso". Economist Don Thompson describes this phenomenon as "buying with your ears". There is value in the name that is completely separate from the work itself. Warhol literally pissed on artworks and sold them because he was so famous. May we all be so lucky.

Adjacent Familiar

Humans like what I call the adjacent familiar — something similar to what they already like but different in an interesting way.

Certain properties of Damien Hirst's spot paintings are the same — the spots within any given painting are the same size, the space between two spots is the same size as the spots, and no two spots have the same color. That is the familiar. But no two spot paintings are the same: the size of the spots varies, the size of the canvas varies, and the arrangement of colors varies. That is the adjacent. Once someone likes the class of spot paintings, they will enjoy seeing the variety of specific instances.

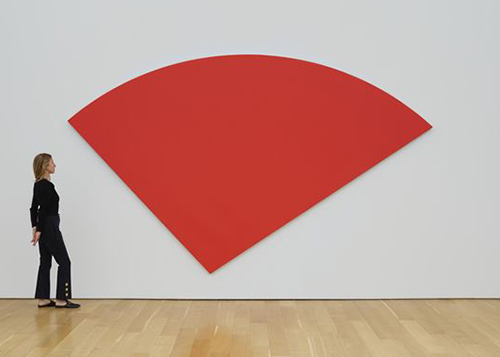

Ellsworth Kelly is one of my favorite artists, and he painted canvases covered in a single pure color. That is the familiar. But the canvases might be smaller or larger, fatter or skinnier, alone or in groups, rectangular or shaped. That is the adjacent. Those variations form a class of paintings, and now that I love the class, I am excited to see new instances of it. This blue is so satisfying! That one has a crazy shape!

I myself paint Honey Bears with different outfits and accessories. Once you like the Honey Bear, you are going to get a kick out of seeing it holding a surfboard, wearing an astronaut helmet, or in lab goggles. The Honey Bear is the familiar, and the outfits and accessories are the adjacent.

I hope that I have also branded a style, and that people who enjoy seeing my Honey Bears also like the lotus flower, elk, and Belted Kingfisher. In this case the style is the familiar, and the different subjects are the adjacent.

Repetition

Let me be very clear: the market rewards you for repetition, not novelty. Or at least it does once you have found Image-Market Fit. People like what is familiar.

Some artists have made careers through simple repetition, but much more rewarding for you and your fans is the adjacent familiar. It is like pop music. People like to be pushed, but only slightly. The images you paint must be different from what has been done before, but once you find something that resonates, you can explore the adjacent territory. The whole body of work gains power as you develop it, and your audience gets to join for the ride, delighting in each new exploration.

If you look at every successful artist, you will find that their work is in some way repetitive. A Keith Haring work is so iconic because he repeated the same style so many times.

Art as Aesthetic Research

In this way, art is aesthetic research. I do not know how a lawn flamingo will look in my style, but I am interested to see, and I paint the lawn flamingo to find out. Your image or style is a constraint, and you apply creativity to explore what variations can be done within that constraint.

Most artists, once they achieve Image-Market Fit, explore the aesthetic territory around that image or style. Damien Hirst has done a round spot painting, a painting with a single spot cut in half, and a painting where a column of spots was offset, forming a spot chain. These are all explorations of the adjacent aesthetic territory / adjacent familiar. If an outcome is compelling, it can be the starting point for further exploration.

Hopefully the image or style you establish has substantial aesthetic possibility. Hirst's spot paintings have a relatively small dynamic range, with each one being fairly similar to the others. He did an admirable job exploring variations, and excitement was no doubt maintained by their beauty, profitability, and that his staff did the physical painting. Eventually, however, he did retire the spot painting series. Ellsworth Kelly, on the other hand, managed to find a style with substantial aesthetic possibility, and he explored that territory for seven decades.

Boredom

Does this repetition get boring? It can. There are, however, two factors that work against boredom.

The first is the size of the aesthetic opportunity. Some styles and images have inherently more opportunities for exploration than others. Being creative within constraints is not boring.

The second factor is the fun of making art people like. The creator of Dilbert, Scott Adams says, "Success does not follow passion, passion follows success". That sounds crazy, but I have experienced it enough to believe it. If I am passionate about something, and it falls flat, then I find myself less passionate. But if I am passionate about something, and it connects with people, then I find myself excited to develop it further. Your work connecting with people is a reward unto itself, and that reward is motivating.

Multiple Bodies of Work

You will still, however, find yourself wanting to try totally new things. If you have success, I would encourage you not to make a hard break from your current body of work but instead to simply start another line of aesthetic research. Try new things, and maybe one of those will connect as well.

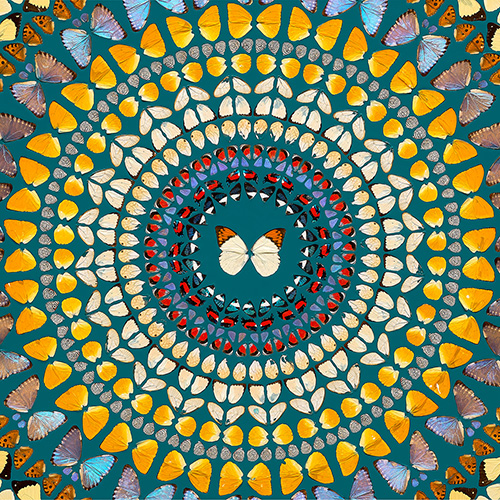

Damien Hirst does not just make spot paintings. He also makes spin paintings, butterfly paintings, medicine cabinets, and animals in formaldehyde vitrines. A spot painting is totally different from a shark suspended in formaldehyde, but both have connected with audiences. I view his large number of styles as a privilege he has earned by being one of the world's most successful artists. Do not develop two bodies of work until you have one with Image-Market Fit. And then add them judiciously.

The Honey Bear is by far the most popular thing I paint, but I have only once had a show of just Honey Bears. There is always something else — duckies, sneakers, birds and flowers, and so forth. In one show I had a Koi painting that was a collaboration with one of my heroes, Jeremy Novy. This series sold out faster than any of the bear editions, which suggests I should think of new ways to remix that idea.

These explorations are all moves into the adjacent familiar of my style, not a move into entirely new aesthetic territory. When I originally wrote this essay I said, "I have ideas for that as well, but I feel I have more to do in my current domain of aesthetic research before I start exploring something entirely different". In the intervening years I have on occasion made things substantially different, such as my sculpture Solar Arch.

Growing tired of painting something people love is a good problem to have. Do not worry about it until it happens. May you be so lucky.